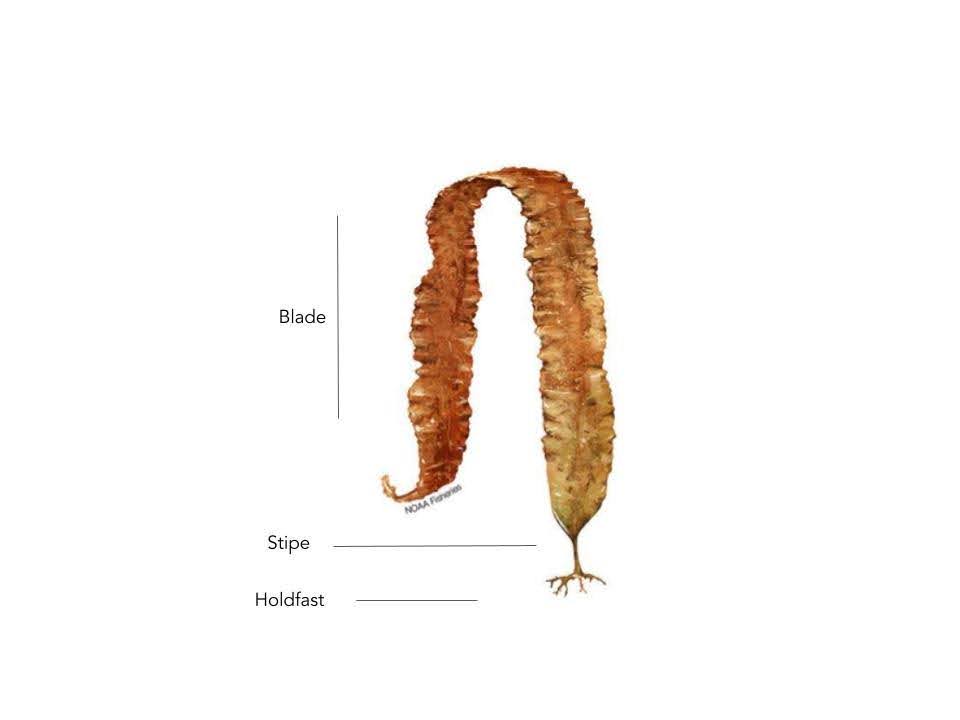

A holdfast, which is a stiff and knotty root-like structure that affixes the kelp to a rock or substrate on the ocean floor

Back to: Kelp Culturing 101

Before getting started with the hatchery process, it’s important to understand the species you’re trying to grow. While there are many types of seaweed that can be seeded on ocean farms, the guidance in the Hub focuses specifically on culturing kelp. Kelp is traditionally cultured by controlling the release of wild reproductive tissue (sorus) in a lab setting to capture the spore release on prepared spools of string. Other species of seaweed may require different methods for growing seedlings – such as grafting into longlines, isolating the tip of the algae for starter cultures, or culturing and breeding gametophyte stocks. While there are many edible seaweeds in the world that are suitable for ocean farming, the guidance here is specifically focused on growing cold water kelp.

What are seaweeds?

Seaweed is a common name for green, red, or brown marine algae. Algae, broadly, refers to a diverse group of photosynthetic aquatic organisms that live in the ocean, as well as in rivers and streams. Algae use chlorophyll to capture the energy of the sun and turn it into tissue to grow. It’s estimated that there are between 30,000 to 1 million species of algae in the ocean. They range from microscopic, primarily single-celled, free-floating organisms—or microalgae—to macroscopic, multicellular organisms—what we commonly call seaweeds. There are three main taxonomic groups of seaweed: red (Rhodophyta), green (Chlorophyta), and brown (Ochrophyta). Seaweed can be found all over the world along the coast in the intertidal and subtidal zone.

What is kelp?

Kelp is a type of large, multicellular, marine brown algae. Many species of kelp grow naturally in the rocky intertidal and subtidal zones of both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. They thrive in cold, nutrient-rich water.

Kelps resemble plants in many ways, with a long stem-like structure (called a stipe) and a root-like structure (called a holdfast), but they’re actually not related at all. Unlike plants, algae cells are undifferentiated—they don’t have true leaves, roots, seeds, or a vascular system. In fact, taxonomically, they belong to an entirely separate kingdom! One of the most unique things about kelps is how fast and large they grow. They are some of the fastest-growing organisms on the planet, developing rapidly from their microscopic spore phase to a mature adult in a matter of months. Depending on the species and location, an adult kelp blade may grow 20 feet long or more in one growing season. Some bull kelp can grow to over 100 feet in length.

The image above identifies the common anatomical features of sugar kelp. Note the three main physical components of the organism.

Kelps Have

-

-

A narrow stipe that forms the connection between the holdfast and the blade

-

Long delicate blades, also called thalli.

Different species of kelp will have different morphologies, causing them to take a variety of shapes, but they all share these three components.

Bull kelp have a very long stipe—at times up to 30 meters long—and a gas-filled structure, called a pneumatocyst, at the top that floats the blades high in the water column. The Alaria species of kelp look similar to sugar kelp, with the addition of small blades near the holdfast, known as sporophylls.